Graphs/Trees for Dummies + BFS

Not just bare theory, but actual traversal code of a tree and graph to have a hands on feeling what these data structures are capable of.

In this article, I’d like to discuss the following:

difference between graphs and trees by example

how to represent directed/undirected graphs and trees in code

how to traverse all of the above with the help of BFS

Graphs vs Trees by Example

Data structures like arrays, lists, sets, and maps don’t have any relationship between entries, they are sitting all together in a data structure without knowing about each other. In the case of graphs and trees, it is different, there are connections between elements. Connections might have directions, and they also might have some weights to represent some value of that connection, for example, the distance between cities.

But what’s the difference between these two data structures. Graphs offer a high level of flexibility in organizing elements and their connections. Trees are far more restrictive, a tree is a strictly defined graph.

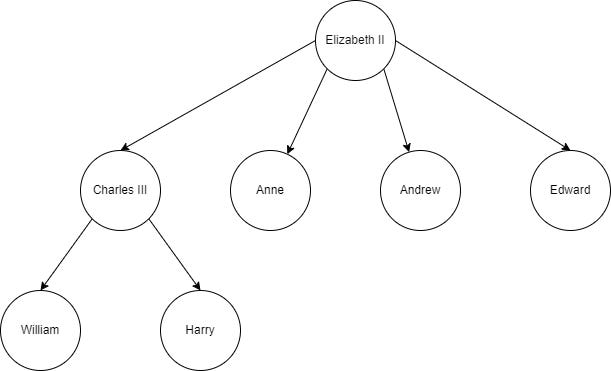

Let’s start with a simple example of a tree:

Here you can see part of the Windsor royal family tree. Each node of the tree represents a family member. There is a hierarchical structure descending from Elizabeth II at the top, connections are called edges, links, or paths. All nodes are connected and the hierarchy of edges in a tree establishes the parent-child relationships between nodes, defines the direction of information flow, and contributes to the acyclic structure of the tree.

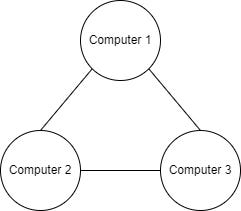

Now let’s see the example of a graph:

Here you can see the computer network graph, each node (or vertex) represents one computer, there is no hierarchy, no starting point, and edges have no direction specified, which means every edge is bidirectional. This kind of graph is called undirected. If the direction was defined, it would be a directed graph and some vertices might become unreachable.

Graphs can have cycles, like the one in our example above. The graph we see in the example is connected, all vertices are connected via edges. Let’s imagine we add Computer 4 and don’t draw any edges from/to it. In this case, we can say that Computer 4 is a disconnected component of a graph of 4 computers.

To summarize:

Graphs

might have several disconnected components

can be directed or undirected

can have weights on the edges

can have cycles

Trees

represent one connected component

are always directed and direction is from a parent node to a child node

can have weights on the edges

can’t have cycles

How to represent a graph

Now we know what is a graph in theory and how to draw it on paper. But how can we represent it in the code? In data structures like arrays, lists, sets, and maps we can always find any element by iterating over all elements. In graphs, where vertices are interconnected and might have cycles, a simple search looks less trivial.

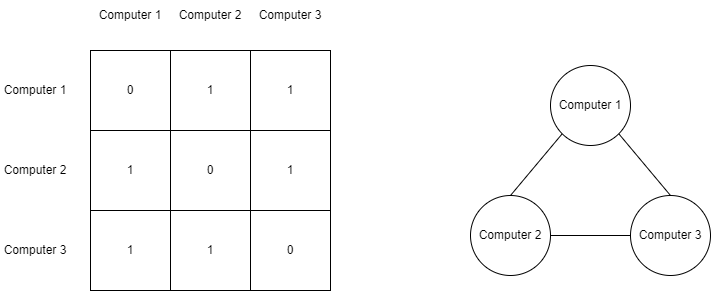

How about we use a 2D array to represent the 3 vertices graph from the previous chapter, a 3x3 array to be exact.

This array is called an adjacency matrix, it is used to show connectivity between vertices. Each row and each column represent some vertex, if their intersection value in the matrix is 0 it means vertices don’t have any edges connecting them, and 1 means there is connectivity. In the case of a weighted graph, instead of 1, we write the weight value.

Now, there are 2 problems with this setup:

It seems unnecessarily complicated when you write code for it, keep in mind we need to map indices of the array to the labels “Computer 1”, “Computer 2” and “Computer 3”. In all the tutorials I saw, the identity of the vertices is usually omitted for simplicity, so you’ll just have vertices 0,1,2 and it nicely fits the example with an adjacency matrix. Here is the code containing both the adjacency matrix and the map of labels to indices. Note: code snippets are in Kotlin

val mapVertexLabelsToArrayIndices = mapOf("Computer 1" to 0, "Computer 2" to 1, "Computer 3" to 2) val adjacencyMatrix = arrayOf( intArrayOf(0, 1, 1), intArrayOf(1, 0, 1), intArrayOf(1, 1, 0) )What if we have a big graph with N vertices and it is sparse, meaning there are not many edges in between the vertices. It will result in a big matrix NxN mostly filled with zeroes, not memory efficient.

We can solve problem#2 by making a list of lists instead of a 2D array, each vertex will point to a list of vertices connected to it. Still, we need to map indices.

val mapVertexLabelsToArrayIndices = mapOf("Computer 1" to 0, "Computer 2" to 1, "Computer 3" to 2)

val adjacencyList = listOf(

listOf(1, 2),

listOf(0, 2),

listOf(0, 1)

)We can avoid these indices altogether by having a map of lists, the so-called adjacency map.

val adjacencyMap = mapOf(

"Computer 1" to listOf("Computer 2", "Computer 3"),

"Computer 2" to listOf("Computer 1", "Computer 3"),

"Computer 3" to listOf("Computer 1", "Computer 2")

)In both the adjacency list and adjacency map, it's easy to include weight information using a more detailed object instead of just an index or vertex label. For a map, it could look something like this:

val adjacencyMap = mapOf(

"Computer 1" to listOf(

Pair("Computer 2", 8), Pair("Computer 3", 10)

),

"Computer 2" to listOf(

Pair("Computer 1", 8), Pair("Computer 3", 15)

),

"Computer 3" to listOf(

Pair("Computer 1", 10), Pair("Computer 2", 15)

)

)To provide context, imagine this number represents the network latency between two computers.

We haven't covered all the ways to represent a graph, such as an incidence matrix or edge list. An incidence matrix is a 2D array, like an adjacency matrix, but unlike an adjacency matrix columns correspond to the edges of the graph. An edge list is a list of tuples with connected vertices labels. What you should take from here is that there is no single correct way to represent the graph, my personal preference falls on the adjacency map, it is memory efficient storing only what is needed and it is rather performant if we use a hash map.

How to represent a tree

We learned that trees are graphs that don’t have cycles, have directed edges, and represent one connected component with a defined root. Also, edges should organize a hierarchical flow of relationships between tree nodes, remember the royal family tree?

We could reuse the way graphs are represented + additional variable to store the label of a root node. Technically it will work, but we won’t have any guarantee that our graph in the adjacency map is a valid tree. Ideally, we come up with a data structure that will enforce the features of trees.

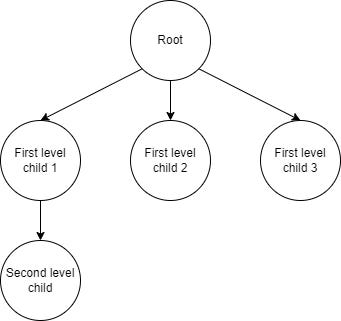

class TreeNode<T>(private val value: T) {

var children: List<TreeNode<T>>? = null

}This one looks pretty good, let’s see it in action:

val tree = TreeNode("Root").apply {

children = listOf(

TreeNode("First level child 1").apply {

children = listOf(

TreeNode("Second level child")

)

},

TreeNode("First level child 2"),

TreeNode("First level child 3"),

)

}This way we can secure the hierarchical structure of a tree with its root. Direction is the only one, from root to children. No cycles are possible here.

Breadth-First Search or BFS

After we’ve learned how to represent graphs and trees in the code, we can proceed to something practical - graphs/trees traversal. Without traversal we can’t even think of using these data structures, for example, how would we find a path between vertices of the graph, or how would we add a node to the tree.

Let’s start with the tree example from the previous chapter.

Now, what would we expect from the traversal of this tree? Let’s make our code print out the visited tree node as proof we reached it. Where do we start? Unlike graphs, trees have a root node, the only node reachable from the beginning. What nodes are reachable from the root node: first level of hierarchy. And after that, we can reach the second level. So, what BFS does as an algorithm is to traverse trees/graphs level by level. Imagine there is a queue for elements to be processed, first, there is a root node, followed by all first-level nodes, and then a second-level node at the tail of the queue. As soon as our whole queue is processed, whole tree is traversed.

class TreeNode<T>(private val value: T) {

var children: List<TreeNode<T>>? = null

fun bfs() {

val queue = LinkedList<TreeNode<T>>()

queue.add(this)

while (queue.isNotEmpty()) {

val currentNode = queue.poll()

println("Visiting ${currentNode.value}")

currentNode.children?.forEach { queue.add(it) }

}

}

}That’s all the code needed to represent the tree and to traverse it. Technically we also use a queue equivalent here, adding newly discovered reachable ones to the tail of the queue, while processing the ones at the front. The result of the code above applied to the tree example from this and previous chapters will print the following:

Visiting Root

Visiting First level child 1

Visiting First level child 2

Visiting First level child 3

Visiting Second level childBFS for graphs

Graphs are more complicated to work with, we can have cycles that will make the queue never-ending if we apply the same approach. We need to keep track of the vertices we’ve visited already and if a vertex was visited already it won’t be added to the queue. Which vertex do we start our traversal with? Any of them. Also, we need to use some way of graph representation, I’d choose an adjacency map.

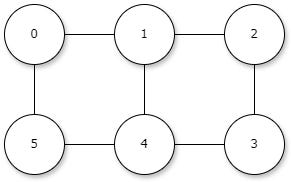

Let’s use the following graph for our example. It is an undirected graph with cycles.

If we start traversing from 0, we add it both to the queue and to the list of visited vertices. Thanks to adjacency map we see next candidates to the queue, 1 and 5, they are both added to the queue since no one of them was visited before. When we are processing 1 we are again suggested to check vertex 0 but we already did, so we don’t add it to the queue. Let’s initialize the adjacency map:

val adjacencyMap = mapOf(

0 to listOf(1, 5),

1 to listOf(0, 2, 4),

2 to listOf(1, 3),

3 to listOf(2, 4),

4 to listOf(1, 3, 5),

5 to listOf(0, 4)

)Now to the code, as discussed the only change here compared to the tree variant is the list of visited vertices.

fun <T> bfs(startingVertex: T, adjacencyMap: Map<T, List<T>>) {

val visitedVertices = LinkedHashSet<T>()

val queue = LinkedList<T>()

queue.add(startingVertex)

visitedVertices.add(startingVertex)

while (queue.isNotEmpty()) {

val currentVertex = queue.poll()

println("Visiting $currentVertex")

for (neighbour in adjacencyMap[currentVertex] ?: emptyList()) {

if (visitedVertices.contains(neighbour)) {

continue

}

queue.add(neighbour)

visitedVertices.add(neighbour)

}

}

}To start processing we need to specify which vertex we want to start from and adjacency map of the graph. We start filling the queue and traversal is ended when there are no elements left in the queue.

Let’s call it for vertex 0:

bfs(0, adjacencyMap)The output will be the following:

Visiting 0

Visiting 1

Visiting 5

Visiting 2

Visiting 4

Visiting 3BFS is spreading in waves, one level after another. What if we use another vertex? Let’s say it is 4. The output will be the following:

Visiting 4

Visiting 1

Visiting 3

Visiting 5

Visiting 0

Visiting 2Since vertices are all connected in this graph and it is undirected we can reach all the vertices every time. Just the order is different because of another starting point.

Summary

We’ve covered a lot of topics, let’s sum up the most important bits:

Graphs are representing networks of vertices connected by edges. They might contain cycles, edges might have weight and/or direction.

Tree is a graph with several restrictions, it has a defined root node, and edges flow from it, from parent to children forming the hierachy. No cycles are possible in this setup. Edges might have weights.

There are multiple ways to represent graphs, adjacency map being subjectively more convenient. Choose the one that fits your task and your graph. Representing tree is rather intuitive and can be done with a custom class.

Breadth-first search is the convenient and easy to code way of traversing a graph or a tree. In case of graphs, don’t forget to keep track of the visited vertices.

Hope it was helpful in your learning journey. Happy coding!